Why Machine Learning is vulnerable to adversarial attacks and how to fix it

Machine learning can process data imperceptible to humans to produce expected results. These inconceivable patterns are inherent in the data but may make models vulnerable to adversarial attacks. How can developers harness these features to not lose control of AI?

The AI Safety debate rages following the lead from top researchers in the field alongside many of today’s technological visionaries, such as those propping up the Future of Life Institute and the Machine Intelligence Research Institute. Through the media, this conversation may appear to sit in a cloud of worry about speculative future-bots that will wipe out humanity.

However, real inklings of how we can easily lose mastery over our AI creations are observed in practical problems related to unintended behaviors from poorly designed machine learning systems. Among these potential “AI accidents” is the case of adversarial techniques. This approach takes, for instance, a trained classifier model that performs well with identifying inputs compared to how a person would classify. Then, a new input comes along that includes subtle yet maliciously crafted data that causes the model to behave very poorly. What is troublesome is that the type of poor behavior is not a reduction in the statistical performance of the model. With such a manipulated input, the model may still classify the object with very high confidence, but the classification is no longer what a human anticipates.

Top-performing and competition-winning image classifiers have been fooled by adversarial attacks. If you look closely at these scenarios, you may find an interesting catch. The offending noise is based on the cost function of the model suggesting that a malicious attacker needs to have the model in hand to figure out how to build the adversarial input. Simply protecting the model from attackers could be a straightforward solution to the problem.

Not so fast.

In 2017, researchers at Penn State, including Nicolas Papernot and Goodfellow, showed that remote adversarial attacks could be performed on ML algorithms considered as a “black-box” – in other words, without access to the model’s training data or its code. This approach uses the idea of transferability where a sample that is trained to mislead one model will likely be able to mislead another model (i.e., one targeted for attack).

Papernot’s team created local image classifier models and trained them to see how modified samples would result in misclassifications. They then took these same adversarial samples (images of stop signs modified in ways imperceptible to human vision) and sent them off to remotely hosted deep neural networks accessible through APIs from Amazon and Google. The same tricky images tricked the remote models as well. They even reported misleading remotely hosted models that included adversarial defense strategies.

(Want to try to break your models with adversarial examples? Try out the cleverhans library developed by Papernot et al.)

All this is a big deal, so what should we do about it? If an attacker can control (or confuse) the classification results of, say, a computer vision model driving your autonomous vehicle to work without needing direct access to the code, then a stop sign may be easily classified as a yield sign. So much for getting to work on time or alive. While a clear problem that AI developers must appreciate, this still represents a defined challenge that should be tractable and solvable. It’s just one more way humans ingeniously hack into other human systems to cause human issues against which humans must defend.

What if this case of adversarial samples is an iceberg tip of something more? Something inherent in the way machines process information? Something beyond human perception?

Just recently, a group from MIT posted a study hypothesizing that previously published observations of the vulnerability of machine learning to adversarial techniques are the direct consequence of inherent patterns within standard data sets. While incomprehensible to humans, these exist as natural features that are fundamentally used by supervised learning algorithms.

In this paper, Andrew Ilyas et al. describe a notion of robust and non-robust features existing within a data set that both provide useful signals for classification. In hindsight, this might not be surprising when we recall that classifiers typically are trained only to maximize accuracy. Which features a model uses to obtain the highest accuracy – as determined by a human’s supervisory labeling – is left to the model to sort through with brute force. What looks to us like a person’s nose in an input image is just another combination of 0s and 1s compared to a chin from the perspective of the algorithm.

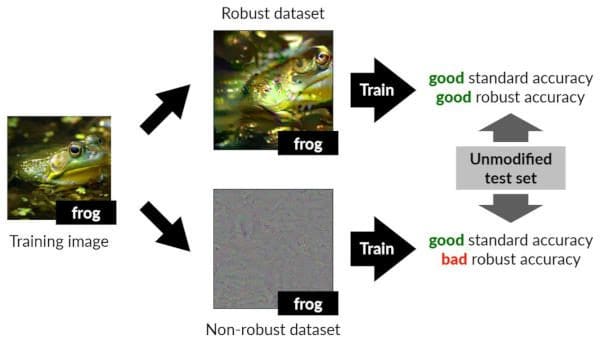

To demonstrate how these human-perceptible and non-perceptible features support accurate classification, the MIT team constructed a framework to separate the features into distinct training data sets. Both are run through the training and are sufficient to classify as expected. The models are seen, as illustrated in Figure 1, to use non-robust features in meaningful ways just as the robust features, even though they look like garbled information to us.

Figure 1. An image of a frog is separated into “robust” features used to train a classifier to accurately identify it as a frog and “non-robust” features that are also used to train a classifier to identify frog accurately, but not when adversarial perturbations are included in the input. These non-robust features used by the model are inherent to the image and not manipulated or inserted by an attacker [from Ilyas et al. with permission].

Let’s be clear on this point again.

Legitimate data is comprised of human-imperceptible features that impact training. These weird features that don’t appear to connect to the appropriate human classification are not artifacts or overfittings but are naturally occurring patterns that are sufficient on their own to result in a learned classifier.

In other words, patterns useful for classification that we as humans expect to see might be found by the algorithm. However, other patterns are being identified that make no sense to us – but they are still patterns that support the algorithm in making good classifications.

Dimitris Tsipras from the MIT team is excited about their result as “it convincingly demonstrates that models can indeed learn imperceptible well-generalizing features.”

While these patterns don’t look like anything meaningful to us, the ML classifier is finding them and using them.

When facing adversarial inputs (e.g., small perturbations in the new data), this same set of nonsensical features breaks down leading to incorrect classification. Now, it’s not only some third-party attacker inserting misleading data into a sample, but it’s a consequence of the non-robust features existing in the real data that makes the classifier vulnerable to an adversary’s taunting.

Recalling the notion of transferability mentioned above from Papernot et al., it’s also these non-robust features existing across datasets that make them sensitive to adversarial examples trained on other models. An adversary trained to break one model will likely break another because it’s messing with the inherent non-robust features found in both models.

So, the notion that supervised machine learning is vulnerable to adversarial examples is a direct consequence of the inherent properties of how algorithms look at the data. The algorithm is performing just fine chugging away at whichever patterns of features lead it to the best accuracy. If an adversary messes with its classification result, then the model still thinks it’s performing quite well. The fact that the result is not what we as humans would perceive is our problem.

To have a bit more human touch, Tsipras said that since “models might rely on all sorts of features of the data, we need to explicitly enforce priors on what we want the model to learn.”

In other words, if we want to create models that are interpretable as far as we are concerned, then we need to encode our expected perceptions into the training process and not leave the algorithm to its own, non-human, devices.

Well, so what if the algorithm is seeing things differently than we do as humans? Why is this unexpected? Is it scary? Is it something we don’t want to see happening?

We know ML processes our world differently than us. Just compare to the foundational notion in NLP where the meanings of words can be extracted not from a memorized dictionary (as we humans do) but from exploring the nearby terms in a human-written text (such as in Word2vec). It should already be appreciated that algorithms running on silicon see information differently than synapses firing in brains.

However, it’s this potential for an alternate, although equally effective, viewpoint that can lead AI down different paths of intention than humans. It’s what might make us lose our control.

From the work of Ilyas et al., a key focus, then, should be to embed human biases into ML algorithms to always nudge them into the direction we expect from our viewpoint. For their future work, Tsipras said, “we are actively working on utilizing robustness as a tool to bias models towards learning features that are more meaningful to humans.”

Building our models to be more human-aligned by including priors during development and training may be the crucial starting point to ensuring we don’t lose our controlling grasp on the future of AI.

So, consider keeping a little touch of “human” in your next machine learning project.

…

Resources cited in this article:

- Amodei, D. et al. “Concrete Problems in AI Safety.” arXiv.org, June 2016.

- Tanay, T. “Adversarial Examples, Explained.” KDnuggets, October 2018.

- Jain, A. “Breaking neural networks with adversarial attacks.” KDnuggets, March 2019.

- Papernot, N. et al. “Practical Black-Box Attacks against Machine Learning.” arXiv.org, February 2016.

- Papernot, N. et al. “Transferability in Machine Learning: from Phenomena to Black-Box Attacks using Adversarial Samples.” arXiv.org, May 2016.

- Jost, Z. “Machine Learning Security.” KDnuggets, January 2019.

- Ilyas, A. et al. “Adversarial Examples Are Not Bugs, They Are Features.” arXiv.org, May 2019.

Related: